Bringing the moths into the light

About This Project

Interdisciplinary research group begins nationwide moth monitoring project with AI analysis

Moths live largely in secret because they shy away from daylight: moths are a species-rich group of insects with around 1,160 species in Germany. These insects are now to be recorded and identified in a broad-based research project. The ambitious goal is to establish a German nationwide monitoring system for these insects and, ideally, to make it permanent. Dr. Gunnar Brehm from Friedrich Schiller University is one of the initiators of the project and is working with research partners in Leipzig, Bonn and other locations. An integral part of the LEPMON project is the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to identify the species, and interested laypeople can also take part. The Federal Ministry of Education and Research is funding the project, which will initially run for three years, with almost 1.8 million euros during the implementation phase; field research is scheduled to begin in April 2025.

The camera light traps deliver huge amounts of data

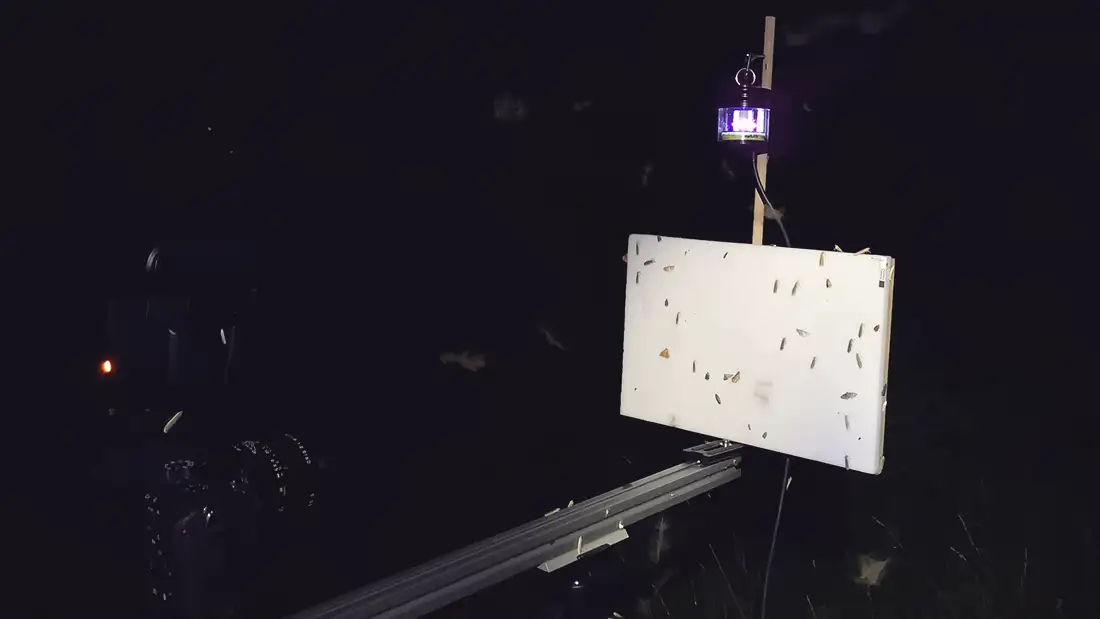

At the heart of the project are camera light traps, which are set up at five locations in each of eight German cities. “A lamp attracts the nocturnal insects and every two minutes all the insects that have settled on a foam plate under the lamp are photographed,” says Gunnar Brehm. The advantage of the system is obvious: although the insects are disturbed, they are not killed and the systems run largely autonomously. Only the data memories need to be replaced regularly.

Traps will be set up in Jena, Dresden, Leipzig, Freiburg/Br., Ludwigshafen, Bonn, Marburg and Bremen. All eight project locations combined will initially produce around 10,000 images night after night, with further locations to be added later. This will generate a huge amount of data. The researchers are using artificial intelligence to analyze this data in a meaningful way.

Dr. Paul Bodesheim, who is researching digital image processing in Professor Joachim Denzler’s group at the University of Jena, is developing an AI system. It is being trained to recognize the species of moths in the photos as accurately as possible. “We use various characteristics of the animals, such as size, shape, color and texture of the wings, to supplement determinations and additional information from experts and interested laypeople alike,” says Bodesheim. In other words, the AI is enabled to recognize differences and similarities by integrating additional knowledge.

Training is carried out using photos from entomologists as well as interested laypeople, such as insect lovers or nature photographers. Collections from universities, museums and other research institutions are also used. In the winter semester 2024/25, a low-budget version of the camera light trap will also be developed as a tool for citizen science. “We are making this somewhat simpler light trap available to interested citizens; it is aimed at associations or school classes who want to take part in monitoring,” says Gunnar Brehm.

Newly immigrated species could be detected by monitoring

The evaluation of the collected data will help to compile an inventory of nocturnal insects in Germany. The participating institutes, such as the German Center for Integrative Biodiversity Research Halle-Jena-Leipzig, are working hand in hand. This will ensure that the wealth of data can be comprehensively evaluated and made available for further research. In this way, the distribution of moths in cities can be investigated as well as the actual number of insects – keyword “insect declines”.

Gunnar Brehm says that as soon as the system is fully developed, nationwide monitoring could be established. This would make it possible to make long-term statements about population trends, and data could also be collected in protected areas. Two possible side effects are conceivable: Monitoring could allow immigrant species to be discovered promptly, but also the mass occurrence of insect pests could be detected quickly.

Contact:

Gunnar Brehm, Dr.

Wissenschaftlicher / technischer Mitarbeiter

Phyletisches Museum

Phyletisches Museum

Vor dem Neutor 1

07743 Jena

Paul Bodesheim, Dr.

Professur für Digitale Bildverarbeitung

Raum 1218

Ernst-Abbe-Platz 1-2

07743 Jena

Date

Dezember 20, 2024